Until the final few seasons, House was one of the better shows on television. Despite a

frustratingly familiar story arc (“Wow, I can’t believe House solved the case

with only five minutes left in the episode”), the writers managed to keep the

medical side interesting and the characters complex and challenging; even House’s

disdain for religion, though frequently hackneyed (faith is inferior to reason:

so brave), served as an interesting counterpoint to his mantra, “Everybody

lies.”

Until the final few seasons, House was one of the better shows on television. Despite a

frustratingly familiar story arc (“Wow, I can’t believe House solved the case

with only five minutes left in the episode”), the writers managed to keep the

medical side interesting and the characters complex and challenging; even House’s

disdain for religion, though frequently hackneyed (faith is inferior to reason:

so brave), served as an interesting counterpoint to his mantra, “Everybody

lies.”

In

the episode “Humpty Dumpty,” House’s boss, Dr. Cuddy, asks her young handyman

to go up on her roof even though he has been complaining of asthma problems. When

he does, he ends up falling off her roof and into House’s care. Cuddy naturally

feels guilt and personal responsibility, which House tactfully attributes to

narcissism: “You can't believe everything is your fault,” he says, “unless you also

believe you're all powerful.” It may be uncouth, but it's also an interesting thought: ultimately, the handyman made the choice to go up on the roof; even though Cuddy shouldn't have pressured him, it was his decision and therefore not entirely her fault.

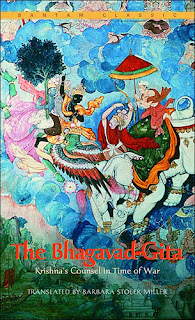

The

bulk of the Bhagavad-Gita is a speech

given by the Indian god Krishna to the fearless young warrior Arjuna who,

before the start of the major battle recounted in the Mahabharata, is suddenly overwhelmed by a moral dilemma: is it not

wrong to kill his enemies – some of whom are his friends and family – even in

the midst of war? Krishna takes this as his starting point in explaining that one must not be concerned with the

fruits of action – its effects and consequences – because only when one is

free from the notion that events are caused by one’s actions rather than by the

natural course of the universe will

he achieve enlightenment.

The Divided Warrior

The Bhagavad-Gita gives us one

of our earliest looks at true hesitation and paralyzing indecision, something that was conspicuously absent

in much of Greek and Latin literature. Whereas the Iliad

is fueled by Achilles’ rage, the driving force here is an interior conflict. In

the Iliad and the Odyssey, a hesitating warrior dawdles

but a moment and requires only the smallest of nudges – usually an appeal to

the gods – to be coaxed back into action. (If anyone knows of examples where

this isn’t the case, I’d be interested to hear them.) Arjuna, on the other hand, requires

much more – around a hundred pages worth of coaxing.

We’ve

all been in Arjuna’s shoes, though perhaps the situation wasn't as extreme. “The flaw of pity blights my very being;

conflicting sacred duties confound my reason.” Pity is a flaw, a blemish, and

yet it is as dear to him as his warrior duty; he does not know what to follow.

In his indecision, he muses, “It is better in this world to beg for scraps of

food than to eat meals smeared with the blood of elders I killed at the height

of their power while their goals were still desires.” He adds, “We don’t know

which weight is worse to bear– our conquering them or their conquering us.”

At

the core of his hesitation is the impenetrability of the future. What will come

of his actions should he take them? Will the world be a better place if he does

his duty, or should he follow his heart’s urgings toward compassion? How is one

to act when there is no objective metric to determine the best course of

action?

The Fruits of Labor

“All undertakings are marred by a flaw, as fire is obscured by smoke.”

“All undertakings are marred by a flaw, as fire is obscured by smoke.”

Seeing

his favorite warrior in such pain, Krishna begins his speech. “Don’t yield to

impotence!” he says. “A man cannot escape the force of action by abstaining

from actions; he does not attain success just by renunciation.” Let us take

this line in two parts. First, action, not one's personal action but action in a

universal sense, possesses a force. In this way, it can be thought of as the

movement of time, the so-called “arrow of time.” Abstaining from action is not

the same as not acting. The latter is impossible if we identify action with an

inexorable force. It is interesting to note that Krishna identifies himself

with this force, the force that will eventually destroy all people and all

worlds, almost like entropy.

In

the second part, we must distinguish between renunciation and relinquishment.

Renunciation is the giving up of something based on one’s desire; it is

equivalent to saying, “I do not wish to participate, and so I will not.” It is

selfish and counterproductive, like a child throwing a tantrum by holding his

breath; though he tries to not participate by renouncing air, he will find that

it is to no avail. Relinquishment, on the other hand, is like saying, “I see the

pointlessness of the endeavor, and so I will not put any stock in it, though I

will still participate.” Krishna calls this giving up the fruits of one’s

actions. “Be intent on action,” he urges, “not on the fruits of action.” Since

we must act – since acting is an inevitable certainty – then let us do so. If,

however, we hope for any particular outcome of those actions, we are being

misled. Here is Krishna again: “A man who sees inaction in action and action in

inaction has understanding among men.” That is, be the person who is detached

from the fruits of his actions and also recognizes that choosing inaction is in

itself an action.

Why

must we avoid the fruits of action? Here is where Krishna starts sounding a lot

like the Stoics. “Contacts with matter make us feel heat and cold, pleasure and

pain.” Emotional feeling here is equated with physical feeling; all comes from

contact with matter. “It is the senses that engage in sense objects… Brooding

about sensuous objects makes attachment to them grow; from attachment desire

arises, from desire anger is born. From anger comes confusion; from confusion

memory lapses; from broken memory understanding is lost; from loss of

understanding, he is ruined.” And if you give a mouse a cookie…

This

is a long chain of conditionals that Krishna confronts us with, and though the

wording is Eastern-flavored, it is ultimately the same old story: the things of

this world will destroy us if we let them. The only answer is to find a way to

resist participation in them. Which brings me to a point that I’ve thought about often when reading this, or Epictetus, or Plotinus, or any of these

philosophers. It seems like the conclusion of all their advice, of their so-called “practical philosophy,” is that the world must be renounced (or relinquished,

whatever) in order to live in the world. But isn’t that a lot like saying the

only way to win is not to play? The insight remains, but it’s not very helpful,

is it? It is as if you and a friend were cornered by a serial killer, and you

ask your friend what you should do, and he says, “Don’t get cornered by a dude

with a chainsaw.” It’s true, he’s right, but it’s highly impractical. The

distinction Krishna draws between renunciation and relinquishment helps a

little, but to detach oneself from the world can’t be the only thing to do when

you live in the world. I just feel

like all these philosophers were the kids who took the ball away and went home

when they started losing the game.

Duty

We’ve

seen a lot of talk about duty in the past; every story of war and battle emphasizes

it. Here, however, it has a slightly different interpretation.

Duty

in the Bhagavad-Gita acquires a more

universalist bent than in the Greeks or the Romans. Barbara Stoler Miller writes in her

introduction, “By performing his [Arjuna’s] warrior duty with absolute devotion

to Krishna, he can unite with Krishna’s cosmic purpose.” Duty, then, begets purpose. It

is assigned to us by nature in the sense that it provides order in a disordered

world, and so to go against duty is to go against the cosmic flow.

Duty is controlled, ordered; “freedom lies,” Miller tells us, “not in

the renunciation of the world, but in disciplined action.” The true way is not

anarchic; we should not cast off our shackles, but have enough discipline

(defined as skill in action) to perform our duty under any conditions. Krishna

tells us this in his own words: “Truly free is the sage who controls his

senses, mind, and understanding, who focuses on freedom and dispels desire,

fear, and anger."

We could talk about Kafka now, but

since his entire oeuvre is basically about blindly doing one’s duty, let's not and say we did.

Lightness

and Weight

My

favorite book – which I haven’t read since high school and should probably

reread if I’m going to continue referring to it this way – is The

Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera, and a lot of his ideas have

echoes in the Gita. I should revise that and say that echoes is not the right word, but

complements. At the crucial moment in Kundera’s book, the narrator interrupts

the action to discuss a German phrase, “Einmal

ist keinmal”: once is not once, that which can happen only once might as

well have never happened at all, the logic being that without an objective way

of judging which course of action is the correct one, we can only reasonably be

paralyzed at all times by indecision. The ultimate lightness of our actions in

the scheme of the universe runs counter to the importance, the weight, that

they exert on our own lives. And if once is all we get to do things right, we might as well get nothing.

Krishna

gives almost an exact opposite reading of the situation. Where Kundera sees no

objective scale, Krishna sees only

objectivity. Duty is the way to free oneself from the burden of not knowing,

since not knowing springs from a sense of disorder and duty brings us closer to

(some form of) cosmic, universal order. Moreover, there is nothing light about

our actions. Kundera sees lightness since our actions make such a small dent on

the universe, but to Krishna, the dent should not matter at all; it should not

factor into our considerations. Worry over the dent is counterproductive

because we should free ourselves from the notion of cause and effect, that our

actions have consequences which are ours and for which we are responsible. “The

practice of true duty,” the introduction tells us, “does not arise from personal

passion but is part of a larger order that demands detachment.”

Perhaps the wisdom that we are to

take away from this is that the path we choose does not matter so much as that

we are on a path. One of my favorite passages from the book makes it clear why: “All undertakings are marred by a flaw, as fire is obscured

by smoke.”

Stray Observations

Stray Observations

- Miller, opens the Gita with a quote from TS Eliot's Four Quartets: “This is the use of memory: / For liberation–not less of love but expanding / Of love beyond desire, and so liberation / From the future as well as the past.”

- There is an emphasis on honest and false feeling. Honest feeling is characterized by involuntary reactions, like the "bristling" of hair on one's arm. A man has no control over goosebumps or the like, and so to convey, for example, Arjuna's true inner conflict, he tells Krishna that his hair is bristling. These opposites, real and feigned emotion, can be contrasted with the other opposites that abound in the text: freedom and control, action and inaction, past and future (cf. the Eliot quote above), and cause and effect.

- Speaking of the translator, I should say a few words about why I chose this translation. One of my Indian students saw me reading this book and told me that it wasn't one of the better translations. Miller seems quite capable; she has impressive credentials, and the blurbs on the back came from some big names. What was important to me, though, was that this edition included a short essay on Thoreau and his reactions to the Gita. Though I haven't specifically mentioned it, the essay was worth the read and certainly colored a lot of what I talked about.

- All this talk about action and inaction makes me think of the art critic Harold Rosenberg talking about Jackson Pollock. The exact quote escapes me, but he saw in Pollock's work the emphasis on action (hence the term "action painting"). Paint drips as he walks about the canvas, creating a visual documentation of his steps and missteps. He goes on to say that action always tends toward perfection, the setting right of what has gone wrong. Action painting, then, can be seen as a record of one's attempts at order. All of this goes nicely with Krishna's speech.

- Let's repeat that quote I like a third time: “All undertakings are marred by a flaw, as fire is obscured by smoke.” Melville, through the narrator Ishmael, makes a similar statement in Moby-Dick, calling the novel a draft of a draft of a draft. Perfection can never be achieved, only approached, and even then only very obliquely. He goes on to mention the cathedral at Cologne, and how it sits unfinished to this day (though I think it's finished now, but let's not let that detract from Melville's point). Even after hundreds of years and generations of workers, the testament of man's devotion to God was not complete. For more on cathedral-building, check out Raymond Carver's short story "Cathedral."

No comments:

Post a Comment